You believe your money is more valuable

Today’s Key Concept

Not all money is created equal.

As consumers, we believe our $5 will take us further than our friends’ $5.

Our own money is perceived as more valuable, as able to purchase more goods and services, than the same amount in somebody else’s hand.

Why is that, and what implications does it have on how we spend it?

What’s Surprising

The common-sense approach would be that $5 is a fixed amount, just as valuable regardless of who owns it. It should be able to buy the same amount of goods.

However, as Polman and colleagues (2018) highlight in the paper, not all money is created equal.

Money acquired through lottery is spent without much thoughts. Money found in an old coat is '“free money.”

There are different “kinds” of money, and this impacts how the money is perceived and spent downstream.

The paper argues that other people’s money is a different kind than our own.

The Study in Brief

Polman and colleagues (2018) believed the main reason behind seeing other people’s money as valuable is the same than the often-repeated driving lesson warning: “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.”

The main concept is psychological distance. The idea that the further something is, the less valuable it appears. Psychological distance has four dimensions, and the paper gives an example for each of them:

temporal (e.g., it could be spent now vs. in the future)

spatial (e.g., it could be held in a bank account here vs. thousands of miles away)

hypothetical (e.g., it could be the prize in a lottery with a 1-in-10 vs. 1-in-10,000 chance of winning)

social (e.g., it could belong to the self or another person)

In this case, the paper argues that because others are socially more distant than us, we will perceive their money as less valuable.

In the first study, hundreds of people were recruited and asked either:

a. “How many of each item do you think you can buy with $50?” or

b. “How many of each item do you think someone other than yourself can buy with $50?”

Faced with the same list of everyday goods, the people receiving with the first question thought they could purchase more goods than the people with question b.

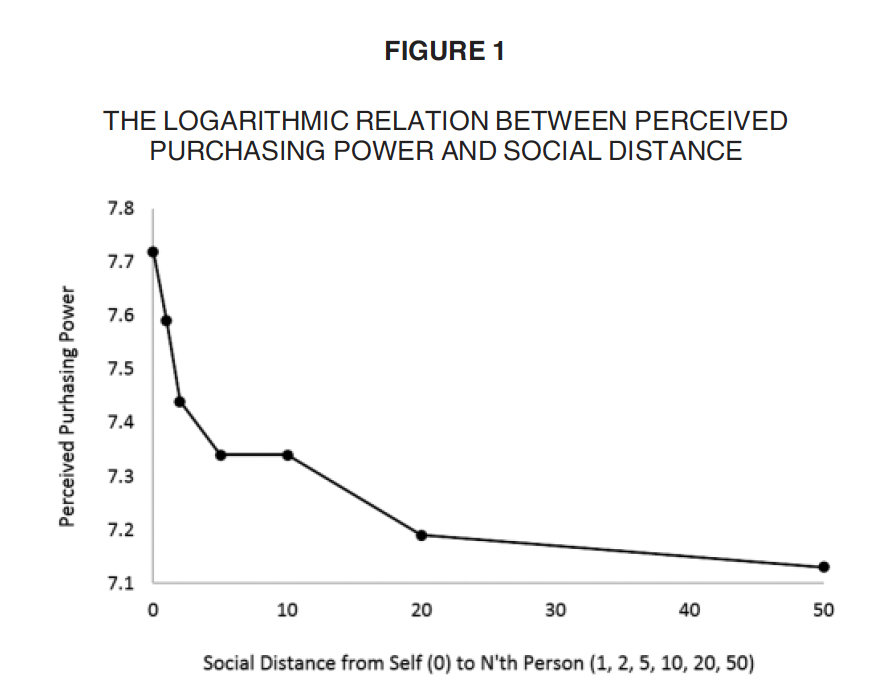

In the second study, they took the question a bit further, recruiting nearly 1000 people online.

They asked each one to think about all of their acquaintances from the closest person (e.g. a spouse) to the less close person (e.g. the bus driver), and to pick the closest, the second closest, the 5th, 10th, 20th and 50th.

Now, they had a sample of participants who had in mind people who were at different social distances to them: would the money of the 5th be more valuable than the money of the 50th closest person?

The study asked how much of everyday goods could the person purchase with $900. The results were clear:

As the above graph illustrates, the further someone is to us, the less we believe the money they have can purchase.

It is almost as if other people’s money is less valuable than our own, and gradually less valuable as they move towards main acquaintances.

How Can You Use It?

This psychological phenomenon is interesting in the context of gift cards, 2-for-1 offers and such social purchases where consumers have to think about what someone else will receive.

As consumers, we might be incentivised to purchase higher-value gift cards if asked to imagine what the recipients might be able to purchase with the amount.

Similarly, if consumers believe a fixed amount will be able to purchase less when in the hands of others, it may be useful in the context of discounts, loyalty programs and referrals as well.

These incentive schemes might be adapted to reflect social closeness, such as family bundles or flatmate bundles. According to the research, $5 given to a family member is more valuable than $5 given to an acquaintance, and so the referral program or discount might be more attractive to the consumer.

All in all, psychological distance is a useful framework to make sure offers and values reach their full potential. They’re not created in a vacuum, but are impacted by who they’re for relative to ourselves.

As the paper concludes:

“In other words, the perceived market value of money itself depends on who owns it. In this way, our research documents a novel way in which the value of money is in the eye of the beholder.”

What’s the Source?

Evan Polman, Daniel A Effron, Meredith R Thomas. Other People’s Money: Money’s Perceived Purchasing Power Is Smaller for Others Than for the Self. Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 45, Issue 1, June 2018, Pages 109–125